Anasazi Woman and He Baby Anasazi Woman and Her Baby

The four of u.s. walked slowly down the deep, narrow canyon in southern Utah. It was midwinter, and the stream that ran alongside us was frozen over, forming svelte terraces of milky ice. Still, the place had a cozy appeal: had we wanted to pitch military camp, we could have selected a grassy banking concern beside the creek, with clear water running nether the skin of water ice, dead cottonwood branches for a burn, and—beneath the 800-foot-high rock walls—shelter from the air current.

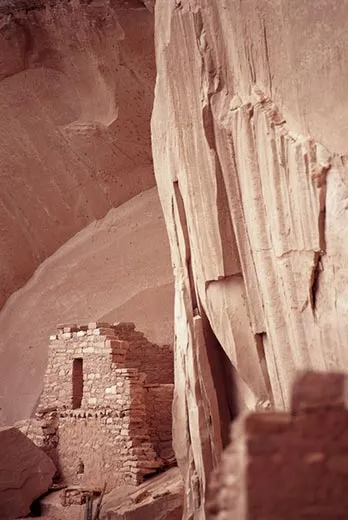

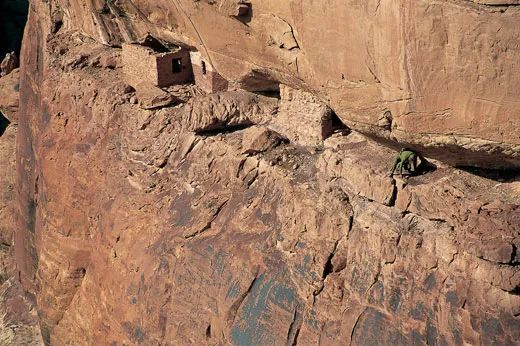

More than vii centuries ago, however, the terminal inhabitants of the canyon had made quite a different determination about where to live. As we rounded a bend along the trail, Greg Kid, an practiced climber from Castle Valley, Utah, stopped and looked upward. "There," he said, pointing toward a almost invisible contraction of ledge just below the canyon rim. "Run across the dwellings?" With binoculars, we could just brand out the facades of a row of mud-and-stone structures. Up we scrambled toward them, gasping and sweating, conscientious not to dislodge boulders the size of pocket-sized cars that teetered on insecure perches. At last, 600 feet in a higher place the canyon flooring, we arrived at the ledge.

The airy settlement that nosotros explored had been built past the Anasazi, a civilization that arose as early as 1500 B.C. Their descendants are today'due south Pueblo Indians, such as the Hopi and the Zuni, who live in xx communities along the Rio Grande, in New Mexico, and in northern Arizona. During the 10th and 11th centuries, ChacoCanyon, in western New Mexico, was the cultural center of the Anasazi homeland, an area roughly corresponding to the Four Corners region where Utah, Colorado, Arizona and New Mexico meet. This thirty,000-square-mile landscape of sandstone canyons, buttes and mesas was populated by equally many every bit xxx,000 people. The Anasazi built magnificent villages such equally ChacoCanyon'south Pueblo Bonito, a tenth-century circuitous that was equally many as five stories tall and contained almost 800 rooms. The people laid a 400-mile network of roads, some of them 30 feet broad, across deserts and canyons. And into their architecture they built sophisticated astronomical observatories.

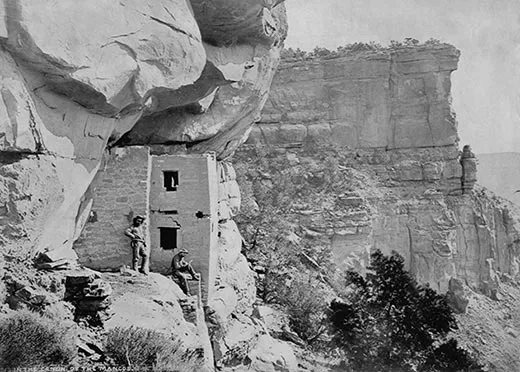

For nigh of the long span of time the Anasazi occupied the region now known as the Four Corners, they lived in the open or in easily accessible sites inside canyons. But about 1250, many of the people began constructing settlements high in the cliffs—settlements that offered defense and protection. These villages, well preserved by the dry out climate and by stone overhangs, led the Anglo explorers who found them in the 1880s to name the absent builders the Cliff Dwellers.

Toward the end of the 13th century, some cataclysmic result forced the Anasazi to abscond those cliff houses and their homeland and to move due south and e toward the Rio Grande and the Petty Colorado River. Just what happened has been the greatest puzzle facing archaeologists who study the ancient culture. Today's Pueblo Indians have oral histories about their peoples' migration, but the details of these stories remain closely guarded secrets. Within the past decade, however, archaeologists have wrung from the pristine ruins new understandings about why the Anasazi left, and the pic that emerges is dark. It includes violence and warfare—fifty-fifty cannibalism—among the Anasazi themselves. "Later about A.D. 1200, something very unpleasant happens," says University of Colorado archeologist Stephen Lekson. "The wheels come off."

This past January and Feb, Greg Child, Renée Globis, Vaughn Hadenfeldt and I explored a series of canyons in southeast Utah and northern Arizona, seeking the most inaccessible Anasazi ruins we could find. I accept roamed the Southwest for the past 15 years and have written a book almost the Anasazi. Similar Greg, who has climbed Everest and K2, Renée is an expert climber; she lives in Moab, Utah, and has ascended many desert spires and cliffs. Vaughn, a bout guide from Bluff, Utah, has worked on a number of contract excavations and rock art surveys in southeastern Utah.

We were intrigued past the question of why the villages were built loftier in the cliffs, but we were every bit fascinated by the "how"—how the Anasazi had scaled the cliffs, allow alone lived there. During our outings, we encountered ruins that we weren't sure we could attain even with ropes and modern climbing gear, the use of which is prohibited at such sites. Researchers believe the Anasazi clambered up felled tree trunks that were notched by rock axes to class minuscule footholds. These log ladders were often propped on ledges hundreds of feet off the ground. (Some of the ladders are nonetheless in identify.) Just they would not take been adequate to reach several of the dwellings we explored. I believe that archaeologists—who are usually not stone climbers—have underestimated the skill and backbone it took to live amidst the cliffs.

The buildings that Greg had spotted were easier to get to than most of the sites nosotros explored. Simply information technology wasn't so like shooting fish in a barrel to navigate the settlement itself. Every bit we walked the ledge of the ruin, the get-go structure we came to was a v-foot-tall rock wall. Four small loopholes—iii-inch-broad openings in the wall—would have allowed sentries to find anyone who approached. Behind this entry wall stood a sturdy building, its roof notwithstanding intact, that adjoined a granary littered with 700-yearold, perfectly preserved corncobs. Further along the narrow ledge, we turned a sharp corner only to exist blocked by a 2d ruined wall. We climbed over it and continued. Twice nosotros were forced to scuttle on our hands and knees as the cliff above swelled toward us, pinching downward on the ledge similar the jaws of a nutcracker. Our feet gripped the border of the passage: one devil-may-care lurch meant certain expiry. Finally the path widened, and we came upon 4 splendidly masoned dwellings and another copious granary. Below united states, the cliff swooped 150 anxiety down, dead vertical to a slope that dropped another 450 feet to the canyon floor. The settlement, once domicile to peradventure 2 families, seemed to exude paranoia, as if its builders lived in abiding fear of attack. Information technology was hard to imagine elders and minor children going dorsum and forth along such a unsafe passage. Yet the ancients must accept done just that: for the Anasazi who lived in a higher place that void, each foray for food and water must have been a perilous mission.

Despite the fright that obviously overshadowed their existence, these concluding canyon inhabitants had taken the fourth dimension to make their home beautiful. The outer walls of the dwellings were plastered with a smoothen coat of mud, and the upper facades painted flossy white. Faint lines and hatching patterns were incised into the plaster, creating two-tone designs. The rock overhang had sheltered these structures and then well that they looked as though they had been abandoned but inside the past decade—not 700 years ago.

Vertiginous cliff dwellings were non the Anasazi's merely response to whatever threatened them during the 1200s; in fact, they were probably not all that mutual in the culture. This became apparent a few days later when Vaughn and I, leaving our two companions, visited Sand Canyon Pueblo in southwest Colorado, more than 50 miles east of our Utah prowlings. Partially excavated between 1984 and 1993 by the non-for-profit Crow Canyon Archaeological Middle, the pueblo comprised 420 rooms, 90 to 100 kivas (hush-hush chambers), xiv towers and several other buildings, all enclosed past a stone wall. Curiously, this sprawling settlement, whose well-thought-out compages suggests the builders worked from a master program, was created and abandoned in a lifetime, between 1240 and about 1285. Sand Coulee Pueblo looks naught like Utah's wildly inaccessible cliff dwellings. But there was a defense strategy built into the architecture nevertheless. "In the late 13th century," says archaeologist William Lipe of Washington State University, "there were 50 to 75 big villages similar SandCanyon in the Mesa Verde, Colorado, region—canyon-rim sites enclosing a spring and fortified with high walls. Overall, the best defense plan confronting enemies was to amass in bigger groups. In southern Utah, where the soil was shallow and food hard to come by, the population density was low, so joining a big group wasn't an pick. They built cliff dwellings instead."

What drove the Anasazi to retreat to the cliffs and fortified villages? And, later, what precipitated the exodus? For a long fourth dimension, experts focused on environmental explanations. Using information from tree rings, researchers know that a terrible drought seized the Southwest from 1276 to 1299; it is possible that in certain areas at that place was virtually no rain at all during those 23 years. In improver, the Anasazi people may have nearly deforested the region, chopping down trees for roof beams and firewood. But environmental bug don't explain everything. Throughout the centuries, the Anasazi weathered comparable crises—a longer and more astringent drought, for example, from 1130 to 1180—without heading for the cliffs or abandoning their lands.

Another theory, put forrard by early on explorers, speculated that nomadic raiders may have driven the Anasazi out of their homeland. But, says Lipe, "There's merely no bear witness [of nomadic tribes in this area] in the 13th century. This is 1 of the nigh thoroughly investigated regions in the world. If there were plenty nomads to bulldoze out tens of thousands of people, surely the invaders would accept left enough of archaeological evidence."

Then researchers accept begun to look for the answer within the Anasazi themselves. According to Lekson, two critical factors that arose later 1150—the documented unpredictability of the climate and what he calls "socialization for fear"—combined to produce long-lasting violence that tore apart the Anasazi culture. In the 11th and early 12th centuries at that place is little archaeological evidence of true warfare, Lekson says, but in that location were executions. As he puts it, "There seem to take been goon squads. Things were not going well for the leaders, and the governing structure wanted to perpetuate itself past making an case of social outcasts; the leaders executed and even cannibalized them." This practise, perpetrated by ChacoCanyon rulers, created a society-wide paranoia, according to Lekson's theory, thus "socializing" the Anasazi people to live in constant fear. Lekson goes on to describe a grim scenario that he believes emerged during the side by side few hundred years. "Entire villages go afterward one some other," he says, "alliance against alliance. And it persists well into the Spanish menstruum." As belatedly equally 1700, for instance, several Hopi villages attacked the Hopi pueblo of Awatovi, setting burn to the customs, killing all the developed males, capturing and possibly slaying women and children, and cannibalizing the victims. Bright and grisly accounts of this massacre were recently gathered from elders by NorthernArizonaUniversity professor and Hopi skilful Ekkehart Malotki.

Until recently, because of a pop and ingrained perception that sedentary ancient cultures were peaceful, archaeologists have been reluctant to acknowledge that the Anasazi could have been violent. As Academy of Illinois anthropologist Lawrence Keeley argues in his 1996 book, War Before Culture, experts accept ignored prove of warfare in preliterate or precontact societies.

During the last half of the 13th century, when war patently came to the Southwest, even the defensive strategy of aggregation that was used at SandCanyon seems to have failed. After excavating only 12 percent of the site, the CrowCanyonCenter teams found the remains of 8 individuals who met violent deaths—six with their skulls bashed in—and others who might have been battle victims, their skeletons left sprawling. There was no evidence of the formal burying that was the Anasazi norm—bodies arranged in a fetal position and placed in the footing with pottery, fetishes and other grave goods.

An fifty-fifty more grisly motion-picture show emerges at Castle Rock, a butte of sandstone that erupts 70 feet out of the bedrock in McElmoCanyon, some five miles southwest of SandCanyon. I went there with Vaughn to encounter Kristin Kuckelman, an archaeologist with the CrowCanyonCenter who co-led a dig at the base of operations of the butte.Hither, the Anasazi crafted blocks of rooms and fifty-fifty built structures on the butte's meridian. Crow Coulee Centre archaeologists excavated the settlement between 1990 and 1994. They detected 37 rooms, 16 kivas and nine towers, a complex that housed perhaps 75 to 150 people. Tree-ring data from roof beams bespeak that the pueblo was built and occupied from 1256 to 1274—an fifty-fifty shorter menses than Sand Canyon Pueblo existed. "When nosotros commencement started digging here," Kuckelman told me, "we didn't expect to find evidence of violence. Nosotros did detect human remains that were not formally buried, and the bones from individuals were mixed together. But information technology wasn't until two or 3 years into our excavations that we realized something actually bad happened hither."

Kuckelman and her colleagues as well learned of an aboriginal legend about Castle Rock. In 1874, John Moss, a guide who had spent time amongst the Hopi, led a party that included photographer William Henry Jackson through McElmoCanyon. Moss related a story told to him, he said, by a Hopi elder; a journalist who accompanied the political party published the tale with Jackson's photographs in the New York Tribune. About a thousand years agone, the elderberry reportedly said, the pueblo was visited past roughshod strangers from the due north. The villagers treated the interlopers kindly, but presently the newcomers "began to fodder upon them, and, at last, to massacre them and devastate their farms," said the article. In desperation, the Anasazi "congenital houses high upon the cliffs, where they could store food and hide away 'til the raiders left." Yet this strategy failed. A monthlong battle culminated in carnage, until "the hollows of the rocks were filled to the skirt with the mingled claret of conquerors and conquered." The survivors fled south, never to return.

By 1993, Kuckelman's coiffure had concluded that they were excavating the site of a major massacre. Though they dug simply 5 per centum of the pueblo, they identified the remains of at least 41 individuals, all of whom probably died violently. "Apparently," Kuckelman told me, "the massacre ended the occupation of Castle Stone."

More recently, the excavators at Castle Rock recognized that some of the dead had been cannibalized. They also found bear witness of scalping, decapitation and "face removing"—a practice that may accept turned the victim'southward caput into a deboned portable trophy.

Suspicions of Anasazi cannibalism were first raised in the late 19th century, simply it wasn't until the 1970s that a handful of physical anthropologists, including Christy Turner of Arizona State University, really pushed the statement. Turner's 1999 volume, Human Corn, documents bear witness of 76 different cases of prehistoric cannibalism in the Southwest that he uncovered during more than xxx years of research. Turner adult 6 criteria for detecting cannibalism from bones: the breaking of long basic to get at marrow, cut marks on bones made past stone knives, the burning of bones, "anvil abrasions" resulting from placing a bone on a rock and pounding it with some other stone, the pulverizing of vertebrae, and "pot polishing"—a sheen left on bones when they are boiled for a long time in a clay vessel. To strengthen his argument, Turner refuses to aspect the impairment on a given ready of bones to cannibalism unless all six criteria are met.

Predictably, Turner's claims aroused controversy. Many of today's Pueblo Indians were deeply offended by the allegations, equally were a number of Anglo archaeologists and anthropologists who saw the assertions every bit exaggerated and role of a pattern of condescension toward Native Americans. Even in the face of Turner's prove, some experts clung to the notion that the "extreme processing" of the remains could have instead resulted from, say, the mail-mortem destruction of the bodies of social outcasts, such as witches and deviants. Kurt Dongoske, an Anglo archaeologist who works for the Hopi, told me in 1994, "As far equally I'm concerned, you lot tin can't show cannibalism until y'all actually detect human remains in human being coprolite [fossilized excrement]."

A few years later, University of Colorado biochemist Richard Marlar and his team did just that. At an Anasazi site in southwestern Colorado chosen CowboyWash, excavators plant iii pit houses—semi-subterranean dwellings—whose floors were littered with the disarticulated skeletons of 7 victims. The bones seemed to bear most of Christy Turner's hallmarks of cannibalism. The squad also constitute coprolite in 1 of the pit houses. In a study published in Nature in 2000, Marlar and his colleagues reported the presence in the coprolite of a human poly peptide called myoglobin, which occurs only in human muscle tissue. Its presence could have resulted just from the consumption of human flesh. The excavators as well noted evidence of violence that went beyond what was needed to kill: one child, for case, was smashed in the mouth so hard with a social club or a rock that the teeth were broken off. Equally Marlar speculated to ABC News, defecation next to the dead bodies 8 to sixteen hours afterward the act of cannibalism "may have been the final desecration of the site, or the degrading of the people who lived there."

When the Castle Rock scholars submitted some of their artifacts to Marlar in 2001, his analysis detected myoglobin on the inside surfaces of two cooking vessels and one serving vessel, as well as on four hammerstones and ii stone axes. Kuckelman cannot say whether the Castle Rock cannibalism was in response to starvation, but she says it was clearly related to warfare. "I feel differently almost this place now than when we were working here," a pensive Kuckelman told me at the site. "Nosotros didn't have the whole film and then. Now I feel the full tragedy of the place."

That the Anasazi may have resorted to violence and cannibalism under stress is not entirely surprising. "Studies betoken that at least a third of the world'due south cultures have practiced cannibalism associated with warfare or ritual or both," says WashingtonStateUniversity researcher Lipe. "Occasional incidents of 'starvation cannibalism' have probably occurred at some time in history in all cultures."

From Colorado, I traveled south with Vaughn Hadenfeldt to the Navajo Reservation in Arizona. Nosotros spent four more than days searching among remote Anasazi sites occupied until the smashing migration. Considering hiking on the reservation requires a allow from the Navajo Nation, these areas are even less visited than the Utah canyons. 3 sites we explored saturday atop mesas that rose 500 to ane,000 feet, and each had but i reasonable route to the pinnacle. Although these aeries are now inside view of a highway, they seem so improbable as domicile sites (none has water) that no archaeologists investigated them until the belatedly 1980s, when husband-and-wife team Jonathan Haas of Chicago'south Field Museum and Winifred Creamer of Northern Illinois University made extensive surveys and dated the sites by using the known ages of dissimilar styles of pottery establish there.

Haas and Creamer advance a theory that the inhabitants of these settlements developed a unique defense strategy. As we stood atop the northernmost mesa, I could run across the second mesa simply southeast of u.s.a., though non the tertiary, which was further to the eastward; yet when we got on top of the third, we could run into the second. In the KayentaValley, which surrounded usa, Haas and Creamer identified ten major villages that were occupied later on 1250 and linked past lines of sight. It was not difficulty of access that protected the settlements (none of the scrambles we performed here began to compare with the climbs we made in the Utah canyons), but an alliance based on visibility. If one village was under attack, it could send signals to its allies on the other mesas.

Now, every bit I sat amid the tumbled ruins of the northernmost mesa, I pondered what life must have been like here during that unsafe time. Around me lay sherds of pottery in a manner chosen Kayenta black on white, busy in an endlessly baroque elaboration of tiny grids, squares and hatchings—bear witness, one time again, that the inhabitants had taken time for artistry. And no doubt the pot makers had found the view from their mesa-summit home lordly, as I did. Only what fabricated the view nigh valuable to them was that they could encounter the enemy coming.

Archaeologists now generally agree about what they call the "push button" that prompted the Anasazi to flee the Four Corners region at the terminate of the 13th century. It seems to have originated with environmental catastrophes, which in turn may accept given birth to violence and internecine warfare subsequently 1250. Still difficult times alone exercise not account for the mass abandonment—nor is it clear how resettling in another location would have solved the problem. During the by 15 years, some experts accept increasingly insisted that there must also take been a "pull" drawing the Anasazi to the s and east, something so appealing that it lured them from their bequeathed homeland. Several archaeologists have argued that the pull was the Kachina Cult. Kachinas are not merely the dolls sold today to tourists in Pueblo gift shops. They are a pantheon of at least 400 deities who intercede with the gods to ensure rain and fertility. Fifty-fifty today, Puebloan life oft revolves around Kachina behavior, which promise protection and procreation.

The Kachina Cult, perhaps of Mesoamerican origin, may have taken agree amidst the relatively few Anasazi who lived in the Rio Grande and Little Colorado River areas nearly the fourth dimension of the exodus. Testify of the cult'southward presence is found in the representations of Kachinas that announced on ancient kiva murals, pottery and rock art panels about the Rio Grande and in south-central Arizona. Such an evolution in religious thinking among the Anasazi further south and eastward might have caught the attending of the farmers and hunters eking out an increasingly drastic existence in the Four Corners region. They could have learned of the cult from traders who traveled throughout the area.

Unfortunately, no 1 can be sure of the age of the Rio Grande and southern Arizona Kachina imagery. Some archaeologists, including Lipe and Lekson, argue that the Kachina Cult arose besides late to have triggered the 13th-century migration. So far, they insist, there is no firm evidence of Kachina iconography anywhere in the Southwest before A.D. 1350. In any instance, the cult became the spiritual center of Anasazi life soon subsequently the groovy migration. And in the 14th century, the Anasazi began to aggregate in even larger groups—erecting huge pueblos, some with upwards of 2,500 rooms. Says Stephen Lekson, "You need some sort of social glue to concord together such large pueblos."

the day after exploring the KayentaValley, Vaughn and I hiked at dawn into the labyrinth of the TsegiCanyon organisation, north of the line-of-sight mesas. Two hours in, nosotros scrambled upward to a sizable ruin containing the remains of some 35 rooms. The wall behind the structures was covered with pictographs and petroglyphs of ruddy brown bighorn sheep, white cadger-men, outlines of hands (created by blowing viscous paint from the oral cavity confronting a hand held flat on the wall) and an extraordinary, artfully chiseled 40-foot-long snake.

One construction in the ruin was the nigh astonishing Anasazi creation I have ever seen. An exquisitely crafted wooden platform built into a huge flaring fissure hung in place more than xxx feet in a higher place u.s., impeccably preserved through the centuries. It was narrow in the rear and wide in the front, perfectly fitting the contours of the fissure. To construct it, the builders had pounded loving cup holes in the side walls and wedged the ax-hewn ends of massive cantankerous-beams into them for support. These were overlaid with more than beams, topped past a latticework of sticks and finally covered completely with mud. What was the platform used for? No one who has seen it has offered me a convincing explanation. As I stared up at this woodwork masterpiece, I toyed with the fancy that the Anasazi had built it "just because": art for fine art's sake.

The Tsegi Canyon seems to have been the last place where the Anasazi hung on as the 13th century drew to a close. The site with the wooden platform has been dated by Jeffrey Dean of the Arizona Tree-Band Laboratory to 1273 to 1285. Dean dated nearby Betatakin and Keet Seel, 2 of the largest cliff dwellings e'er congenital, to 1286—the oldest sites discovered and so far within the abased region. It would seem that all the strategies for survival failed afterward 1250. But before 1300, the last of the Anasazi migrated south and e, joining their distant kin.

"War is a dismal study," Lekson concludes in a landmark 2002 newspaper, "State of war in the Southwest, War in the World." Contemplating the carnage that had destroyed Castle Stone, the fear that seemed congenital into the cliff dwellings in Utah, and the elaborate alliances developed in the KayentaValley, I would have to agree.

Yet my wanderings this past winter in search of 13th-century ruins had amounted to a sustained idyll. However pragmatic the ancients' motives, terror had somehow given birth to dazzler. The Anasazi produced keen works of fine art—villages such every bit Mesa Verde's Cliff Palace, hallucinatory petroglyph panels, some of the virtually cute pottery in the earth—at the aforementioned time that its people were capable of cruelty and violence. Warfare and cannibalism may have been responses to the stresses that peaked in the 13th century, but the Anasazi survived. They survived non only whatsoever crisis struck soon later on 1250, but also the assaults of the Castilian conquest in the 16th century and the Anglo-American invasion that began in the 19th. From Taos Pueblo in New Mexico to the Hopi villages in Arizona, the Pueblo people today nevertheless dance their traditional dances and still pray to their own gods. Their children speak the languages of their ancestors. The ancient culture thrives.

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/riddles-of-the-anasazi-85274508/

Post a Comment for "Anasazi Woman and He Baby Anasazi Woman and Her Baby"